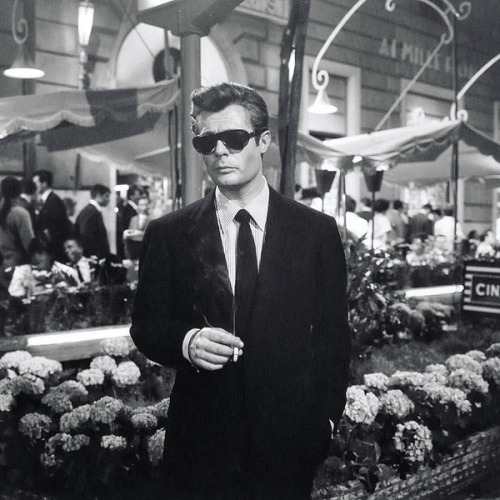

Dark suit, black shades, a cigarette, a Triumph sportscar, and the Eternal City in all of its baroque theatre. It has been sixty years since La Dolce Vita (The Sweet Life) changed cinema forever; Italian director Federico Fellini’s fourth film, and the one which would propel him to international celebrity (meanwhile, making leading man Marcello Mastroianni an icon.)

The story revolves around Marcello Rubini, an unfulfilled journalist sulking (and sleeping) his way around Rome, in three acts which unfold with Caligulan hedonism and high-class scandal. Our cynical journo feels himself drifting further from reality, from his literary aspirations, and deeper into excess. It might be called ‘The Sweet Life’, but don’t be fooled. This is ironic. The good stuff is largely on the surface, while the truth simmers underneath, finally boiling over with murder and adultery—sometimes fizzling away in disappointment. The sweet life can be sexy; it can also be pathetic.

The great movie critic Roger Ebert described it as a ‘favorite film’. In his review, which is more of a retrospective of life lived viewing La Dolce Vita, he suggests how – when younger – he wanted to be Marcello (who wouldn’t?) But over time, his tastes changed. He saw the main character as irredeemable, perhaps too far gone. By his forties, Marcello was a friend, and when Mastroianni died, the character ascended into immortality—in part because of his style.

This outfit is forever seared into celluloid history: a dark wool suit, a white or striped shirt, black tie, and a pair of black monk-straps. Thus, an icon was born (this isn’t the only La Dolce Vita style piece out there, it certainly won’t be the last.) This is also, apparently, the first time international viewers became aware of the ‘Italian Cut’, which is to say: slimmer and less formal or structured than the English. Along with his famous tailoring, Mastroianni wore what appeared to be women’s sunglasses (Persol, in fact.) His choice was not accidental, rather everything Marcello wears is soaked in allegory, like the waters of the mysterious Trevi Fountain he enters to embrace his ‘ideal woman’ (a voluptuous Anita Ekberg.) Shrouded in dark tones, Marcello remains cryptic and guarded. His ambitions and insecurities are buried by his outward appearance. By the end of the film, our hero replaces his serious, black suit for a white one. He ditches the tie for a neckerchief, and swaps a white shirt for a polo—it’s still elegant, but more hip. Likewise, his personality shifts: first from sullen, or cynical and then to absurd and comical. Things have changed. It doesn’t take the clothes to realise this, but it certainly confirms our worst fears: that Marcello caved in to excess. Mastroianni himself suggested in an interview that every outfit was ‘intentional and had meaning’, and the film went on to win an Oscar for Best Wardrobe that year—perhaps for these reasons.

Even with all the allegory, it’s still an incredibly stylish flick. Fellini wanted us to admire Marcello. This meant making his image desirable, too. Case in point: after first viewing in my teens, I went out and bought a cheap and badly-fitted version of his dark outfit (complete with polyester tie), enamored by what I assumed it represented. Isn’t this what all serious, gloomy, misunderstood creatives wore in exotic locales like Rome? Maybe not. Looking back, it was more ‘getaway-driver chic’ than Sweet Life; and when finally, someone asked if it were a Reservoir Dogs costume, I sold it online. But I’ve never stopped trying to find ways to copy this look.

You can kind of do it now. Over the past few years, black tailoring has become more acceptable outside of funereal settings. And of course, there’s always charcoal—a staple single-breasted suit color that most men should own; if only because both the jacket and trousers can be paired with endless other garments, too. Watching La Dolce Vita again, sixty years on, is a reminder that Mastroianni’s hyper-simplistic wardrobe is as timeless as the Eternal City itself.

The charm, though—that’s Marcello’s. You can’t buy that.